Stephen Cairns and Jane M. Jacobs are posing questions about buildings’ lifespans that may make many more traditional architects squirm. The Singapore-based professors of architecture recently published Buildings Must Die, a book that examines what happens when buildings meet their ends, and the effect those inevitable “deaths” can have on our notions of architectural creativity. They explore ways to begin building with the goal of creating malleable neighbourhoods that can be adjusted over time to meet a variety of different purposes. In a recent interview with SCOPE (condensed below), Cairns and Jacobs discussed their ideas on creation and destruction.

Most buildings will stand, as designed, for only a relatively short time. They may become obsolescent relative to current needs and get demolished; they may decay and fall apart through wear and tear, or collapse. It is true there are many buildings that are relatively long lasting, but most of those are in a perpetual dynamic with destructive forces. That such buildings stand is a testament to the maintenance regimes that stave off the end. In other cases, the force of endings is absorbed into the aesthetics of the building, and they stay in place as ruins. The processes that erode, compromise or destroy buildings offer important provocations for architecture, which should not be overlooked or wished away. What Buildings Must Die does is link this previously disparate set of architectural examples to a proposition about the values that should lie at the heart of architectural creativity and practice.

We use the language of dying in the title to provoke a rethinking of how buildings are in the world, how they are conceived, made, inhabited, how they wear in and wear thin. In this sense, we’re interested in disturbing the casual assumption that buildings have life.

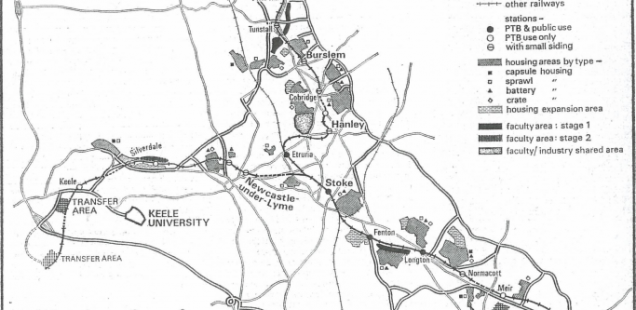

Many architects do think about design and creativity in ways that broach endings. English architect Cedric Price, for example, designed a famous [but never built] science and technology university—the Potteries Thinkbelt—amongst the decaying industrial infrastructure of North Staffordshire. He mixed fixed structures with more ephemeral and temporary structures, such as fold-out decks and inflatable buildings. He understood that different parts of the site would be used with different intensities over time, and that the architecture could be designed to come and go as needed. In preparing for this project, Price modeled the differential rates of use and decay in great detail, charting how the buildings would function through time—including when they would cease to be needed, and so cease to be.

Other architects have designed in collaboration with the forces that work to end buildings. Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron have conducted many experiments on the theme of decay by investigating the bio-receptivity of building materials. In the 1980s and ‘90s, they consciously exposed their buildings to a controlled kind of decay, which produced a hyper-patinated aesthetic. More recently, the interest in sustainable architecture has given designing with a building’s end in mind a new imperative. For example, the so-called Design for Deconstruction (DfD) approach, is precisely about designing for the disassembly of buildings when their original use expires.

The idea of creative birthing of designs is very embedded in architectural pedagogies still, where there is enormous emphasis on creativity and originality. There are certain aspirations and expectations embedded in pedagogies, and replicated in professional architectural discourse and professional practice. But there are serious counter-trends, and these are getting stronger and more coherent. And they have been given a new moral imperative by two contradictory contextual facts: one being the rapid and voracious cycles of creative destruction generated by capitalism, the other being the need for more sustainable and secure futures. Both of these contexts require architecture to think differently about what design is, and how the designed object will be in the world.

The idea of creative birthing of designs is very embedded in architectural pedagogies still, where there is enormous emphasis on creativity and originality. There are certain aspirations and expectations embedded in pedagogies, and replicated in professional architectural discourse and professional practice. But there are serious counter-trends, and these are getting stronger and more coherent. And they have been given a new moral imperative by two contradictory contextual facts: one being the rapid and voracious cycles of creative destruction generated by capitalism, the other being the need for more sustainable and secure futures. Both of these contexts require architecture to think differently about what design is, and how the designed object will be in the world.